1940s

It was almost as though Mr. Sinclair and his team had a crystal ball.

Seeing Hitler’s rise to power in Germany and foreseeing a conflict, Sinclair set five programs in motion by 1941 that allowed the company to continue to grow.

- Sold its European marketing subsidiaries at a profit of about $1 million – which meant Sinclair lost nothing to Hitler during World War II.

- Anticipated the need for 100-octane gasoline by experiments with alkylation and polymerization processes, beginning in 1937. When war came, Sinclair was able to quickly expand its production of aviation gasoline.

- Stepped up oil exploration in Venezuela from 1937, discovering the Santa Barbara field before U.S. entry into the war. By 1945, this new crude oil source contributed 27,000 barrels daily to U.S. operations, helping offset acute shortages at home.

- Augmented its obsolete tankers with 10 fast new vessels, delivered in 1941 and 1942. Of these, eight survived the war, giving Sinclair economical ocean transport during the postwar readjustment.

- Built a new pipeline linking the Eastern Seaboard with the Ohio River, serving the Allegheny region and Washington, D.C., when other transport was preempted for military uses.

Sinclair’s war effort made up 24 percent of its total business.

- One of the largest producers of 100-octane gasoline, which was critical for combat planes.

- Supplied 42 million gallons of military oils and greases in 1944.

- Met many new demands of arctic and desert performance, six-mile-high altitudes and frictions never before encountered in jeeps, tanks or submarines.

- Built and operated a butadiene plant to provide the U.S. government with raw materials for synthetic rubber.

- 348 million gallons of navy fuel in 1944.

- 450 million gallons of regular grade gasoline for military and government use.

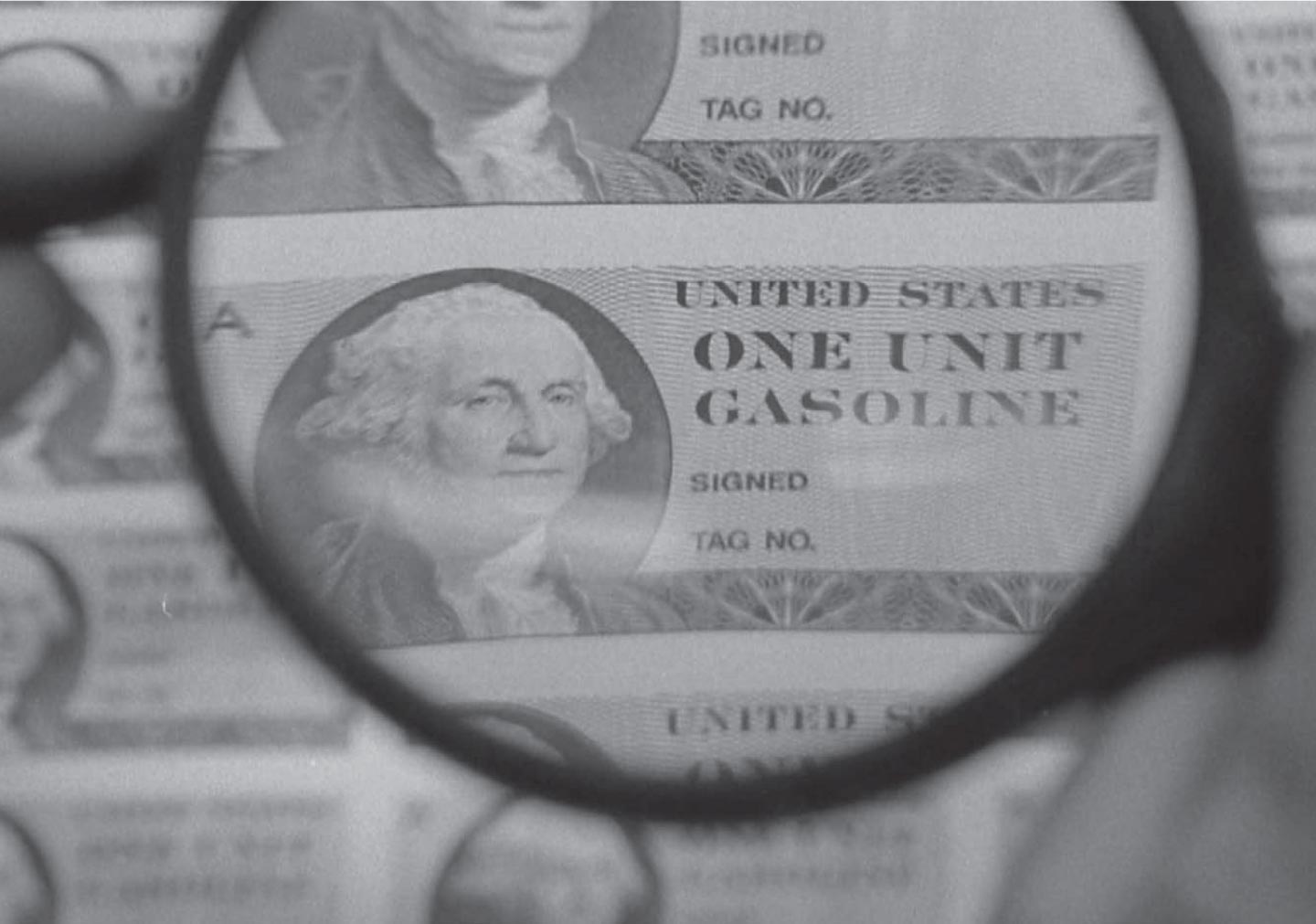

The rest of Sinclair’s business was servicing the home front – keeping the business up despite shortages and rationing. Fortunately, government regulation ended price wars and stabilized costs, while promotional expenses were negligible.

Hundreds of women trained as service aides in retail stations while the men were off at war, and a new products pipeline spurred retail growth throughout the middle-Atlantic states, the Pennsylvania steel towns and the nation's capital.

Thus in the stress of war, Sinclair was able to build for the return of peace. Net earnings averaged a record $21 million during the war. The holding company also regained its name and again became the Sinclair Oil Corporation.

The war ended – and civilian demand boomed.

Two weeks after victory in Japan, Sinclair's military deliveries were cut by 75,000 barrels a day – about one-fifth of capacity. By the end of 1945, only six percent of Sinclair business was in war contracts.

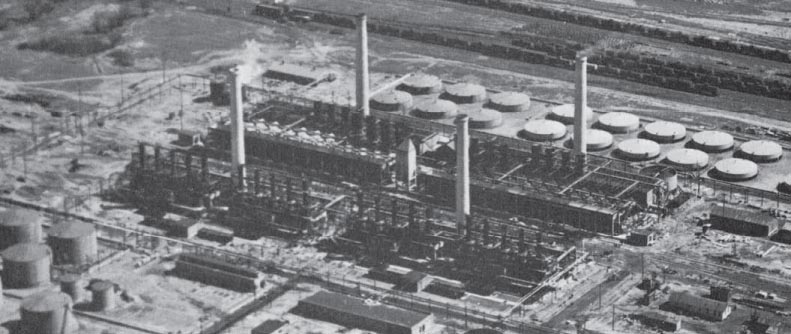

Fortunately, new technology created by the war effort, plus a huge push toward suburban life, increased demand for formerly marginal products like diesel fuels, kerosene, natural gas and liquid petroleum gases. Sinclair's management adjusted to the new needs by budgeting $90 million to renovate the refineries, service stations and terminals, and pipelines.

But the postwar inflation affected pipeline and refinery construction, deep well drilling, and labor costs, as well as gasoline prices.

A Town Called Sinclair

Sinclair acquired the refinery in Parco, Wyoming, during the Depression. On Jan. 1, 1942, the town population voted to change its name to Sinclair, and to this day, the town retains its name and Sinclair still runs the refinery.

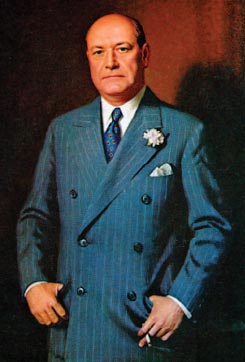

After 33 years of almost total control, Mr. Sinclair retired.

At the close of 1948, Harry Sinclair relaxed his grip for the first time, receding to the perimeter as chairman of the board.

No one quite knew how the corporation had survived its first score of years, except on Mr. Sinclair's audacity. He left a legacy including $700 million of assets for 99,500 stockholders and 21,000 employees. His was the most extensive petroleum complex to bear its founder's name.

But more than that, he bequeathed the tradition of fierce independence.

However, when Percy C. Spencer took Mr. Sinclair’s place as president, the crude oil shortage was acute. Only a genius for tight operation could keep Sinclair competitive.

“The past year was the most prosperous in our history … Our problem now is the most efficient and economical use of these facilities. This task I am turning over to Mr. Spencer and the younger men in the company.”

Harry Sinclair, 1949